On Traditional territory

The Church of the Holy Trinity is on the territory of the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee and, most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. This territory is covered by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Haudenosaunee, the Ojibwe and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the lands and resources around the Great Lakes.

A presence in The Ward

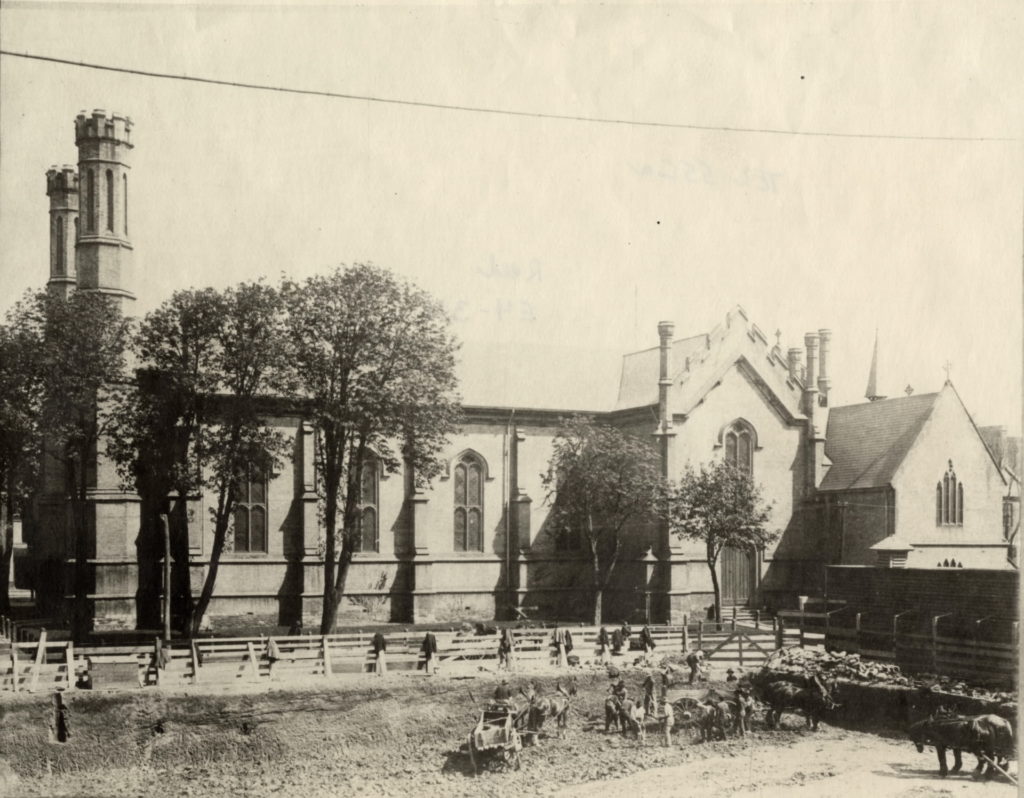

The Church of the Holy Trinity opened in 1847 following the gift of an anonymous donor (later revealed as Mary Lambert Swale of Settle, England and likely also her sister Eliza who was still alive at the time of the bequest). The bequest stipulated that all pews were to be free and unreserved forever. The architect was H.B. Lane, who also designed Little Trinity (on King Street) and St. George the Martyr.

The new church was built on the edge of town using mostly local brick and timber. The area quickly developed and came first to be known as Macaulaytown and then as St. John’s Ward or “The Ward.” The area was home to immigrants, escaped slaves, and other marginalized people of Toronto.

An expression of the Social Gospel

During the Depression era of the 1930s, the church became known as home of the social gospel for the way in which it spoke to the concerns of the city’s unemployed and homeless. That commitment was reflected in a warm welcome to community activists in the 1960s, who incubated sentiment for urban reform. This was also a period of welcome for Vietnam War resisters including a time in which they were housed in the space.

A site of struggle with developers

During the 1970s, with the support of the larger community, the congregation successfully fought off attempts to have the church torn down to facilitate the Eaton Centre development. The efforts of the congregation not only preserved the church’s current location but also led to the establishment of Trinity Square Park.

On May 9, 1977 a fire destroyed nearby buildings and caused extensive damage to the church itself. In the wake of the fire, there was a large degree of community support, and the necessary repairs were made.

Out of concern for the lack of affordable housing in the downtown core, Holy Trinity insisted that land for affordable housing should be made available in return for land that had been lost through the development. This then led to two affordable apartment buildings. Mary Lambert Swale, named for the Holy Trinity benefactor and foundress, is a 75-unit building at 269 Jarvis St and John Frank Place is a 138-unit apartment building at 80 Dundas Street East named for the Depression-era social activist priest of Holy Trinity. Although we were instrumental in their establishment, Holy Trinity no longer has any operational oversight of either complex.

Beginning in the year 2000, the congregation worked with the Toronto Community Labyrinth Network and the City to establish a labyrinth in the Square. This was permanently built by 2005.

A home for diverse communities

From the early 1970s, Holy Trinity has been a transitional home to fledgling congregations of diverse backgrounds, including Coptic, Armenian, and Japanese communities.

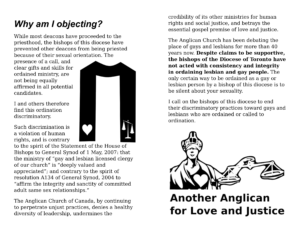

The parish has a long-standing engagement to the rights and determination of 2SLGBTQ+ people and families – it is personal for many of us. We were the home of the first gay and POZ dances in Toronto and have supported and led many other aspects of this struggle including marriage equality, right to ordination and public office, and the visibility of gender non-conforming and trans people. We have rallied for change within the church and governance at all levels, to ensure that our communities are represented within our faith and society.

In 2007, Holy Trinity was joined by the Hispanic congregation of San Esteban who continue to meet on Sunday afternoons. Holy Trinity and San Esteban have several shared services throughout the course of the year, including a unity service during Pentecost. After a decade of partnership and community development, the communities continue to strengthen their bond.

More recently, Holy Trinity has worked to forge partnerships with Indigenous communities, including hosting Toronto Urban Native Ministry‘s offices, and working with elders and community members to support efforts towards justice and reconciliation.

Over the years, Holy Trinity has engaged with Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist and Traditional community partners in interfaith study and celebration and in building relationships.

Over its century-and-a half history, often in strong contrast to the society around it, the Church of the Holy Trinity has consistently offered itself as both home and ally to marginalized communities. This has created tension with a range of actors from Anglican establishment to municipal officials to real estate developers.